As the World Economic Forum suggests gender parity is 200 years away, a look at how researching and writing about women from the past 600 years give me purpose and motivation, and constantly remind me that another 200 years is far too long.

By Victoria Martínez

If you have read anything on this blog, you’ll know that I almost never break into the first person. This post is the exception because today, International Women’s Day, and this month, Women’s History Month, are very important to me, both professionally and personally.

Although I don’t limit my efforts as a historical researcher and writer strictly to women’s history, it is the part of my work about which I am the most interested and passionate. Women in history are underserved and poorly represented, even today. Through my writing and research, I strive to be an advocate for both historical and modern women.

The theme of International Women’s Day 2018 is #PressForProgress. InternationalWomensDay.com elaborates:

“With the World Economic Forum’s 2017 Global Gender Gap Report findings telling us that gender parity is over 200 years away – there has never been a more important time to keep motivated and #PressforProgress. And with global activism for women’s equality fueled by movements like #MeToo, #TimesUp and more – there is a strong global momentum striving for gender parity.”

The historical women I have chosen to highlight in this post exemplified this spirit in their own times, often against greater odds and stronger resistance than most of us face today, and almost always at a much higher personal cost. Like most women, I am indebted to the actions of these women, and feel deeply that researching and writing about them is one way that I, too, can press for progress.

In researching, studying and writing about these women, my primary goal is not to entertain readers, but to help perpetuate the spirit and courage in action that they exemplified. I have a special interest in women who have been historically “mishandled” in some way, both intentionally and unintentionally, in their historical treatment. Although this can be said of most historical women, the ones I have highlighted here are just a few of those I have personally have written about with the goal of contributing to improving and correcting the historical narrative.

My purpose in writing this rare personal essay is to provide some insight into why I have chosen to research and write about these particular women who, in the spirit of International Women’s Day, pressed for progress.

Margrete Valdemarsdatter of Denmark (The Lady King Who United Medieval Scandinavia)

In studying history, I come across a lot of incredible people who, through blood, sweat and tears, at some point earned honorifics like expert, connoisseur, visionary, dreamer, philosopher, hero, warrior, and so forth. Often, these badges of respect were conferred on them only after their death, or, in the case of most women in history, only grudgingly, if at all.

So it is a major source of irritation to me when I return my attention to the modern world and find – usually on social media – any number of self-professed “experts” and “visionaries” mixed in among a plethora of casually-proclaimed “dreamers” and “philosophers.” This cheapening of terms that should be hard-earned and, preferably, granted by others, is one of those things that can send me through the roof with frustration.

And don’t even get me started on the fact that far too many deserving women in history have never even been granted such terms of respect, while anyone with a LinkedIn profile and a keyboard can claim the honor. No. Just no.

I’m sorry, but if a 14th century Scandinavian woman who had the male establishments of three countries proclaim her “the husband and guardian” of their kingdoms, and who consolidated her power so effectively over those three countries that she united them under her singular power didn’t give a damn that she had no formal title or honorific to match her astonishing accomplishments, what makes Joe Schmo feel entitled to call himself a “visionary” when looking for a job in telemarketing?

I’m not saying that there’s anything wrong with Joe Schmo. He’s probably a really nice guy. But I can almost guarantee you that he’s not a visionary. Especially not when compared to Margrete Valdemarsdatter, whose best title, in my opinion, is the one given to her by an antagonist: “The Lady King.”

Edith Wharton (The Lesbian and the Novelist Who Escaped the Gilded Age)

It’s not for the reason you are probably thinking that I have studied and written about Edith Wharton. Yes, I love her novels, especially The Age of Innocence, The Buccaneers, and The House of Mirth. But even more than that, I love what she had to say about women’s equality in the United States a century ago. Not least because many of her statements still resonate today.

“No nation can have grown-up ideas till it has a ruling cast of grown-up men and women; and it is possible to have a ruling caste of grown-up men and women only in a civilisation where the power of each sex is balanced by that of the other,” Wharton wrote in 1919.

As an American woman who has chosen to live much of her adult life outside of the United States, I feel a certain kinship with Wharton, who found in France a place where women were treated with more dignity and respect than in the United States. Wharton felt that: “Compared with the women of France the average American woman is still in the kindergarten.” She elaborated: “The reason… is that all their semblance of freedom, activity and authority bears not much more likeness to real living than the exercises of the Montessori infant.”

A century later, women in the United States have come a long way, as have their rights and freedoms. But life in other countries has demonstrated to me quite clearly that women and women’s rights in these countries surpasses the United States to a greater extent than I had previously realized. Living in Sweden, a country that is solidly feminist in its politics and attitudes but still presses hard for further progress, has especially made me realize where I personally had it wrong in my beliefs about the state of women’s progress in the United States. Again, in Wharton’s words:

“How much longer are we going to think it necessary to be ‘American’ before (or in contradistinction to) being cultivated, being enlightened, being humane, & having the same intellectual discipline as other civilized countries? It is really too easy a disguise for our shortcomings to dress them up as a form of patriotism!”

Mary Wollstonecraft (The Scandinavian Salvation of Mary Wollstonecraft)

Speaking of living in Sweden, you won’t ever hear me telling you that life is perfect. Problems are problems no matter where we live, even if they vary a bit from place to place. In particular, adjusting to life in a new country can be extremely challenging, especially when dealing with other transitions and priorities.

Not long after we moved to Sweden, as I was struggling to adapt and adjust from full-time parenting to re-establishing my career, I discovered a side of the great English feminist philosopher Mary Wollstonecraft that was both intellectually surprising and immensely comforting to me.

In 1795, at a time of intense despair and struggle in her life, Mary Wollstonecraft arrived to Sweden to begin a journey through Scandinavia that would help her pull herself from the depths of despair and produce one of her finest works. Her experiences and the book that she wrote about them marked a turning point in her life that helped her finally find peace and happiness in her life.

As I read this work, Letters Written During a Short Residence in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark (1796), I was inspired to follow in her footsteps both literally and figuratively. As I considered my struggles in comparison with hers and visited some of the places in Sweden she had written about, I felt a sense of empowerment and “sisterhood” that surpassed anything I felt reading her great work, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman.

Say what you will, but Mary Wollstonecraft was the friend I needed to help me move more confidently into my second year in Sweden.

Elena Lucrezia Cornaro Piscopia, Stefania Wolicka-Arnd, Helen Magill White, Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander, Georgiana Simpson and Eva Dykes (Beyond Inspiring: History’s Female PhD Pioneers)

If Mary Wollstonecraft helped me get through my first year in Sweden, these are the women who are helping me get through my second. Each and every one of them was a pioneer in women’s struggle to obtain equality in advanced education.

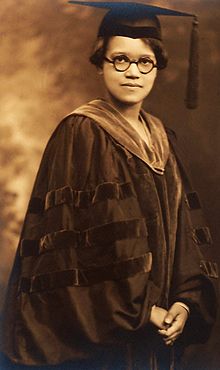

From Elena Lucrezia Cornaro Piscopia, the first woman in history to earn a Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) degree in 1678, to Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander, Georgiana Simpson and Eva Dykes, the three women who share the distinction of becoming the first African American women to earn their PhDs in the United States in 1921, these women keep me persisting in the pursuit my goal of earning my PhD in history.

With them in mind, the work I put into achieving my goal is a drop in the bucket. Although several aspects of my personal situation – including that I am an immigrant to Sweden – and the peculiarities of the Swedish academic system itself mean that just getting a position as a PhD candidate is very difficult, I realize that I am in a very advantageous position compared to and because of the efforts of all of these remarkable women.

If I ever need a reminder of this fact, I only need to read the words of Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander – the first African American woman to earn a PhD in economics:

“I knew well that the only way I could get that door open was to knock it down; because I knocked all of them down.”

***

Main image: A group of amazing women who make me want to fight for their memories and in their names every day. (From left) Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander (Beyond Inspiring: History’s Female PhD Pioneers), Olympe de Gouges (Condemn Her Actions to Silence Her Words), Princess Zahra Khanum “Taj al-Saltaneh” (“Princess Qajar” and the Problem with Junk History Memes), Margrete Valdemarsdatter (The Lady King Who United Medieval Scandinavia), Natalie Clifford Barney (The Lesbian and the Novelist Who Escaped the Gilded Age).